We were sitting at the kitchen table, a book from an early reader phonics series in front of us. I was pointing to each word, as he sounded them out. In some cases he relied on memory, in other places he he practices sounding out and blending new words. The magic happened a page or two into the story, the words started coming out faster, one after another, his mind grabbing on and grasping the process of reading. suddenly he hit his stride. The wheels were churning and the story unfolded without me saying a word.

"He's doing it! He's doing it," my mind was SCREAMING. "My kid can read! He Can Read!!"

I wanted to jump up on the table and dance for an hour. I wanted to call my husband and tell him to grab a bottle of champagne on the way home. I wanted to throw my son into the air and twirl him around the kitchen. I was filled with absolute, pure joy and amazement. He rocked my world in that moment.

It is the most amazing thing to watch and I've now watched it happen twice: that moment when a child starts reading with fluency . You can actually see the "click, click, click" become a more fluid read, read, read. And then he's out of the gate.

My excitement was about the magnanimity of the moment, a moment that took place at a kitchen table. Whatever else he may or may not be able to do in life, he can read. He has acquired the skill that will enable him (eventually) to open up any book he chooses and to read. He has left the life of illiteracy and the possibilities for him are endless. He will have access to books, access to ideas, and ways to learn. He will forever forward know how to read (unless he is abducted by aliens that void his memory or he suffers permanent amnesia). We never hear stories of people unlearning how to read in their native tongue do we?

If he wants to learn about ancient civilizations, learn how to build a boat or rebuild a 1957 Thunderbird, if he wants to understand macroeconomic theory, study art history or agriculture or physics, or read the Bible, for all these things he will turn to written word. All of the words that have been set down in stone and on papyrus and paper and Kindle are his to peruse. If he lets them, words and the ideals they set out will shape his life, his character, his destiny.

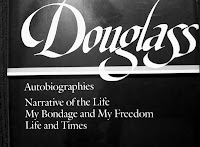

In his autobiography My Bondage and My Freedom, Frederick Douglass wrote some of the most beautiful passages on the meaning and power of literacy and some of the most heart wrenching passages on his journey to learn how to read and open the doors of knowledge. Douglass would covertly learn to read at the age of 13 and in doing so he acquired the words to counter the arguments and evil that sustained slavery. "I saw through the attempt to keep me ignorant," he wrote, reflecting on the desire by slave owners to keep slaves from learning to read.

"Every increase of knowledge, especially respecting the free states, added something to the almost intolerable burden of the thought--"I am SLAVE FOR LIFE," Douglass wrote.

Douglass received a few reading lessons from the wife of his owner after he went to live in Baltimore. But the owner quickly put an end to these lessons, viewing it as too dangerous to educate a slave. When the lessons ended, Douglass understood even more why he needed to continue to learn to read. Having already learned the alphabet, it was the first shaft of light pointing to so much more.

In teaching me the alphabet, in the days of her simplicity and kindness, my mistress had given me the "inch," and now, no ordinary precaution could prevent me from taking the "ell."Douglass knew he needed to learn how to read so he started trading bread for reading instruction from other children in the streets.

Seized with a determination to learn to read, at any cost, I hit upon many expedients to accomplish the desired end. The plea which I mainly adopted, and the one by why I was most successful, was that of using my young white playmates, with whom I met in the streets, as teachers. I used to carry, almost constantly, a copy of Webster's spelling book in my pocket; and, when sent of errands, or when play time was allowed me, I would step, with my young friends, aside, and take a lesson in spelling. I generally paid my tuition fee to the boys, with bread, which I also carried in my pocket. For a single biscuit, any of my hungry little comrades would give me a lesson more valuable to me than bread.My children will never progress to literacy from desperation, the way Douglass did. They will read with vigor, they will read for joy, they will read to assuage their curiosity, they will read to fuel their passion, they may even read to unveil the world's tragedies and horrors (they may read Douglass' biography). They will read with overwhelming support from their parents and teachers. They have come to their literacy-right-of-passage as young children through hard work but without the dark overtones of terror and fear. They will read in the light and be rewarded, not in the shadows fearful of punishment. In the monumental moment when my son began to read fluently he was given a kind of freedom that will one day give him the power to turn dreams into reality. He won't need to dream of being a free man but maybe his dreams will be just as big and just as righteous.

At dinner the other night, I asked my 7-year old daughter what she would do if she had to choose between bread (food) and a book. This is a difficult choice for an energetic, pixie-sized girl who consumes massive amounts of food each day and is also an avid book lover who reads multiple chapter books on a good day. She squinted and thought, hand on her chin, then said, "I'd choose the book, because if I was a bookworm I could eat it after I finished reading it!" My husband and I burst out laughing at the sharp and quirky mind on display.

I asked my daughter if she knew anything about Frederick Douglass. She asked if he was a black man. I said yes, he was a slave and lived before she was born. She nodded and said "He was a man of great importance in American history." I agreed and told her the story about how he traded bread for reading lessons.

"And the moral of the story is you shouldn't choose the important things, you should choose the really important things," my daughter concluded.

Bravo, sweetheart, bravo!

No comments:

Post a Comment